The following essay by Jeffrey K. McCrary was published in the Shawnee Trails Sierra Club Quarterly Newsletter, March-May 2021.

“I realized that if I had to choose, I would rather have birds than airplanes.” Charles A. Lindbergh

One of the pillars of the legal framework of protection of the environment in the US is also one of the oldest: The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA). This law has an enormous reach in the protection of birds and their habitats throughout the country, but its application has varied throughout its long history, and is currently facing a dramatic reduction in its scope, which obliges all of us to offer our public comments regarding the proposed changes, as will be addressed below.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, wildlife hunting was already voracious in America. It was not only a sport; it was a lifestyle and a livelihood for many. Even Teddy Roosevelt’s uncle wrote an influential guide to hunting shorebirds, an activity that would irk most hunters today. The Great Auk, a penguin-like species ranging throughout the North Atlantic, had already been wiped from the planet half a century before, to provide down for bedding.

Even the birds of Illinois were dramatically affected. A rapidly growing country with ever-increasing demands for food brought the Passenger Pigeon to extinction by the second decade of the twentieth century; even the unpalatable Carolina Parakeet was extirpated from the planet, by a combination of hunting to protect crops from predation, and by habitat loss as forests were cut to grow crops. Both species, once found throughout the state, were doomed before legislation could control hunting and other activities on a nationwide basis.

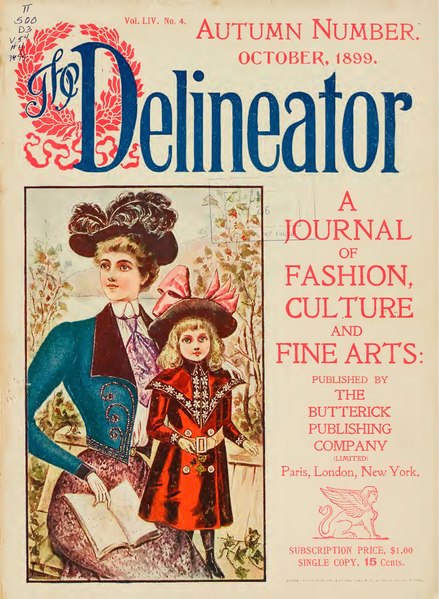

Birds were also targeted by the hunters of the day to supply bird feathers for women’s attire. The targeted birds included ducks, gulls, terns, sandpipers, egrets, and herons. The fashion frenzy captured New York and London milliners. Feathers, and even body parts such as wings were incorporated into hats and other clothing. Even hummingbird beaks were used in earrings! Among the most affected birds was the Snowy Egret; its feathers sold for 34 dollars an ounce. This elegant species continues to nest in the wetlands in southern Illinois, but its numbers still have not recovered to levels noted before the impacts of feather hunting more than a century ago. Another migrating visitor to Illinois, the Eskimo Curlew, never recovered from the hunting of this period, and has since been declared extinct.

The evolution of activism and legal wrangling within the US that led to the MBTA is itself a worthy read, which can be found in several sites, such as here. A fundamental issue with the inadequacy of the first attempts at restricting the mass slaughter of birds was that the great majority of the birds targeted for the fashion industry were migratory, so state-level, and even country-wide, laws were not sufficient to stop or regulate the trade in birds. The MBTA became a law that is backed by four international treaties with four countries⸺ Russia, Japan, Canada, and Mexico ⸺to protect all migratory birds in each respective country.

This legislation likely would have never come about without a groundswell of activism to propel the issue into the governmental consciousness across the continent and into Europe and Asia. The principal actors in bringing the plight of birds to protection were women. Some names must be mentioned: Florence Merriam Bailey composed a book entitled Birds through an Opera-Glass and other ornithological books to promote the cause of appreciating birds in their natural habitat; Harriet Hemenway and her cousin Minna Hall organized among socialite circles in Boston against the slaughter of birds for the millinery trade.

The impact of the MBTA on hunting over its first years was direct, with measurable success noted on several birds, including the Snowy Egret, Wood Duck, and the Sandhill Crane, all of which migrate along the Mississippi Flyway through southern Illinois. This flyway is basically the path of the Mississippi River, a straight route, uninterrupted by mountains, connecting Canada to the southern US, and where many birds fly onward to Central and South America. This flyway is occupied by as many as 40 per cent of the migrating waterfowl and shorebirds in the United States. As birdwatchers know, the complex of protected areas along bottomland the Mississippi River and its tributaries make for great viewing of migrating birds. Along this route are areas protected by a range of municipal, state, and federal laws. It merits mentioning the names of some of these wonderful natural places that have been made public lands for conservation purposes: Shawnee National Forest; Big Muddy National Fish and Wildlife Refuge; Middle Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge; Cypress Creek National Wildlife Refuge; Cache River State Natural Area.

The scope of land management strategies that have been implemented to benefit migratory birds is immense, incorporating public and private lands throughout the state. But, regardless of the regulatory or management status or ownership of the land in question, the MBTA applies. Its text bears repeating: “it shall be unlawful at any time, by any means or in any manner, to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, attempt to take, capture, or kill, possess, offer for sale, sell, offer to barter, barter, offer to purchase, purchase, deliver for shipment, ship, export, import, cause to be shipped, exported, or imported, deliver for transportation, transport or cause to be transported, carry or cause to be carried, or receive for shipment, transportation, carriage, or export, any migratory bird, any part, nest, or egg of any such bird, or any product”.

Migratory bird species in the US today, recognized and defended by this law, number 1093 strong today. Two other substantive laws currently protect birds in a similar way: the Endangered Species Act which protects some 35-40 bird species today, about half of which inhabit only Alaska or Hawaii; and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. As a result, the MBTA is monumental, as only a few of the migratory birds protected under it would receive relief otherwise. All of these three laws which protect specific bird species in the US differ from laws and regulations concerning protected areas and conservation easements, because they protect birds on all US territory, regardless of the ownership or disposition of the land. Exceptions and/or permits are provided in MBTA for certain activities, however, such as for hunting of traditional game birds, eagle feathers for certain Native American uses, some military activities, and for certain special purposes such as relocation of animals in a property undergoing development and control of threats to airplanes by birds such as geese.

As could be imagined, this law has found plenty of use and has encountered fierce objection since its inception. The MBTA decisively took the rights of legal interpretation and enforcement on migratory birds away from states and into the hands of the federal government under the Treaty Clause of the US Constitution. Decades after its implementation, its reach advanced from hunting to other activities that incidentally kill birds, as well.

Industrialization of the country had created numerous death-traps for birds. Beginning in the 1970’s, this law was used to penalize companies for activities such as pesticide spraying where birds were killed even though the killing was unintentional and ancillary to the activity penalized. Indescribably horrible oil spills such as the Exxon Valdez in 1989 and the Deepwater Horizon in 2010 were prosecuted using the MBTA, resulting in huge penalties.

Birds are killed in enormous numbers today by such monuments to modernity as power lines, oil tanks and ponds, shrimp and fish farms, wind farms, solar energy farms, farms, glass-and-steel buildings, air traffic, and pet cats. Some of these activities have become regulated, with guidelines being developed in consensus between the respective sectors and government (for example, this guideline exists for wind energy). However, we all know that industry does not implement even an inexpensive fix to save birds just because birds are nice to save. The guidelines and participation are the direct outcome of liability to companies and individuals for their behavior. When millions of dollars are at stake, one can only expect a company to act against the greater good of the public interest, unless forced otherwise. In the interest of a proper environment in which more migratory birds do not end up on the Endangered Species Act rolls, or worse, we need good laws to protect them.

And many companies have challenged the MBTA, with considerable success, on the issue of intent. As stated above, companies and individuals whose behavior kills birds must be found to include one or more of the verbs, “pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill,” with respect to migratory birds to be prosecuted under the MBTA. Several defendants have argued that the MBTA does not hold them responsible because they never aimed a gun at a bird; they simply conducted an activity whose objectives did not include killing birds, and hence, none of the verbs mentioned above applied to them.

Sometimes, courts have sided with the accused that their actions which prejudiced birds were not intentional toward the birds, but rather that the bird deaths were incidental and thus, not within the purview of the MBTA. Numerous law analyses have been made on this complex issue, dating back at least into the 1970’s, some of which can be found here, here, here, and here. It is interesting that several defendants over the years escaped liability under this law, but not the two Big Oil violators mentioned above, perhaps because of the overwhelming environmental consequences and other kinds of liabilities that limited their capacity to argue this angle sufficiently. However, until the previous presidential administration, the US Fish and Wildlife Service maintained consistently that industrial and commercial activities lay within the purview of MBTA, in spite of disagreements in the courts.

The recently concluded presidential administration maneuvered to stop all MBTA-related prosecutions for incidental impacts on birds in 2018; the Fish and Wildlife Service attempted to change the regulations on MBTA implementation during its last week in office in 2021 to exclude incidental impacts on birds. Your Sierra Club has worked hard to oppose the dismantling of this law. This seemingly dismal turn of events, however, could be regarded as a black cloud with a silver lining. The current presidential administration has temporarily blocked the implementation of this suspension, which was to begin February 8, and has lengthened the call for public comments until March 1, 2021.

Please submit your online comments by March 1st, and consider an online webinar hearing! Go online to the Federal Registrar: http://www.regulations.gov. Enter into the Docket Search space (or just click on the link): FWS-HQ-MB-2018-0090.

Click Comment Now! Enter your pre-written, original, signed, letter, with the following heading/address:

Public Comments Processing

Attention: FWS-HQ-MB-2018-0090

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, MS: JAO/3W

5257 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, Virginia 22041-3803

- Request the withdrawal of the proposed rule to limit the effects of the MBTA to bear only on “intentional” takes of migratory birds.

2. State the importance to you that the MBTA has provided protection of birds from “unintentional” takes.

3. Request that the law be strengthened to include language that unequivocally ensures accountability for all actions that harm migratory birds, whether for sport or commercial activity, without regard to the primary intention of the action.